State seeks salt reduction. Can it change fast enough?

By Ry Rivard

Ahead of the 1980 Winter Olympics, local officials decided they had to fight one of the very things drawing people to Lake Placid from around the world—the snow.

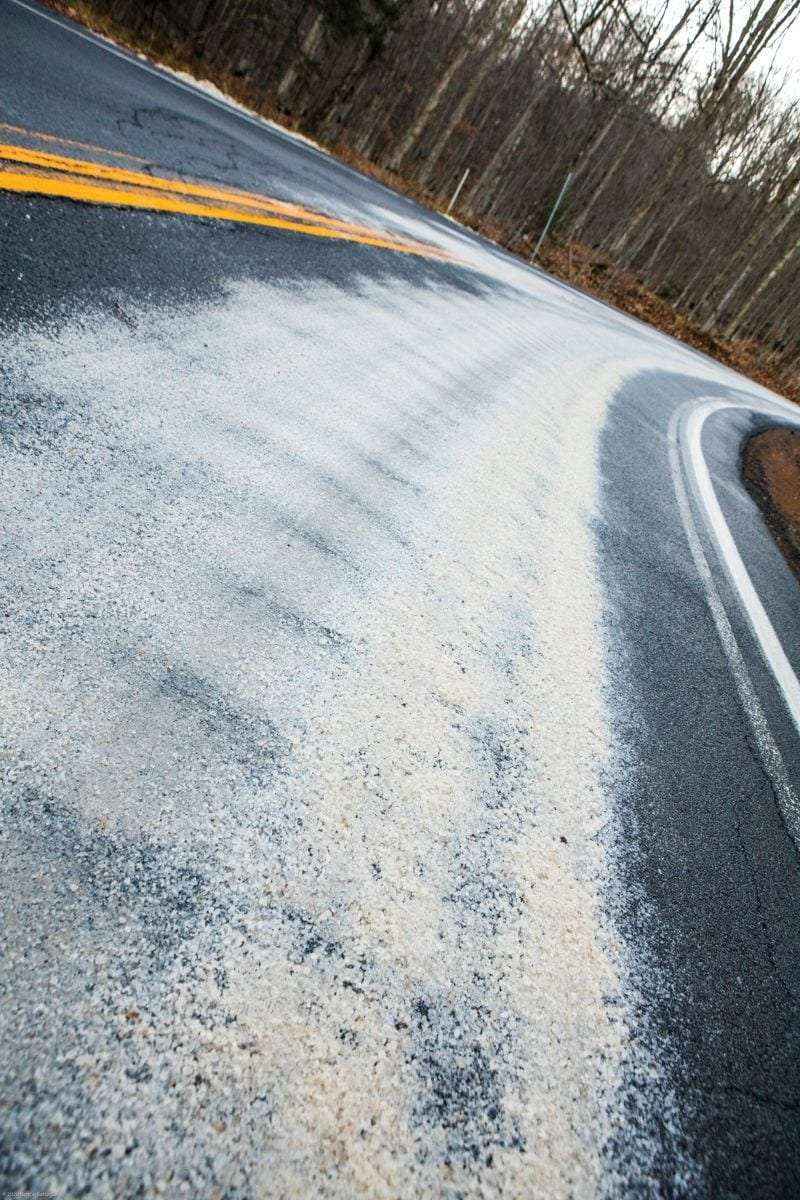

To ease the commute through the Adirondacks, they kept roadways clear by dumping unprecedented amounts of salt on them.

The Lake Placid Olympic Organizing Committee’s plan called for about six times as much salt to be used that winter as in winters past.

Olympic organizers knew this could be a problem, but they expected the salting to be a one-and-done thing. Clear the roads for the tens of thousands of people traveling here for the first time, then go back to the way things used to be.

Ironically, the snow never came. A snow drought struck in 1980. Artificial snow was used for the first time at an Olympics.

But the idea to salt the roads stuck, and the salting never stopped.

Before then, Adirondack roads weren’t cleared all the way to the blacktop every time it snowed. People drove slower. They had snow tires. Highway departments put sand on top of snow to increase traction.

Heavy salting could cause long-term environmental damage, the U.S. Department of Commerce wrote in an environmental study for the Olympics. That 200-page document from summer 1978 is one of the few accessible pieces of paperwork left that confirms what many old-timers remember: The Olympics. That’s when the salting began.

The chemical properties of salt help it fight off snow and ice but harm metal, meaning salt can ruin cars, appliances and plumbing. At high enough levels in drinking water, salt is dangerous to human health. It raises blood pressure and leads to heart attacks, strokes and kidney disease.

Before the 1980 Games began, officials worried about all of this. Roadside plants might die from too much salt. Lakes might choke on too much salt. Salt could run into drinking water supplies.

It may have taken years, but that’s all happened now. Road salt helped kill 90-year-old birch trees along Cascade Lakes on the way to Lake Placid, according to a state-funded report by the Clarkson Center for the Environment. Salt now makes conditions in Mirror Lake, the lake that runs along downtown Lake Placid, dangerous for trout.

And, as the Adirondack Explorer has reported over the past year, salt has seeped into drinking water supplies, made water unsafe to use and threatened people with financial ruin.

By 2015, the Fund for Lake George, a nonprofit watchdog for the lake that anchors one of the country’s desirable lakefront property markets, said salt was “the acid rain of our time.”

Now, years later, the state may get serious about the problem.

In early December, Gov. Andrew Cuomo approved a bill that would require the state to form a task force to study the damage done by salt in the Adirondacks.

“Road salt application, while necessary for public safety, can also pose a risk to the public health and environment when used improperly or to excess,” Cuomo said in a statement when he signed the bill, which was backed by Adirondack lawmakers and pushed by local environmental groups.

The new law isn’t the first stab at trying to understand the damage. The New York State Department of Transportation has conducted a string of pilot projects going back nearly 40 years looking at ways to reduce salt use, including a few recently in the Adirondacks.

But those haven’t resulted in wholesale changes to how it clears roads.

Perhaps that’s because New York law insulates highway officials who are to blame.

Perhaps it’s because the clear roads that were promised ahead of the Olympics became a gold standard for public safety that’s hard to back away from. Want two-day delivery? Salt. Want to jump in the car for a quick trip to Plattsburgh in the middle of February? Salt. Want tourists in their little sedans to come spend money in Keene Valley? Salt.

Now, the department “looks forward to working with the task force to explore new ways to balance public safety, the environment and public health in the Adirondack Park,” DOT spokesman Joseph Morrissey said in an email.

To others, those ways have been explored and the path is clear: Want to use less salt safely? Use less salt now.

Kevin Hajos, the superintendent of Warren County’s public works department, is treating 100 miles of roads with a saltwater brine and using more advanced plows that do a better job clearing roads. The brine is less salty than pure salt and it doesn’t immediately bounce off the road into nearby streams, like salt crystals dumped from the back of a truck do.

“We’re so far ahead of where the state is at this right now,” Hajos said.

He has been helped along the way by Phill Sexton, a consultant who has become the go-to person for reducing salt pollution in the North Country.

Before he founded his consulting business, WIT Advisers, Sexton left a job helping lead one of the largest snow removal companies in the country and went to Harvard to study salt.

There, Sexton wrote a thesis about the “quiet yet significant environmental epidemic” of salt pollution.

Now, Sexton tries to get highway departments and snow removal contractors to use less salt. In phone conversations over the past year, he can be both abstract and practical. One minute, he’ll compare the arms race for clear pavement to the greening of American lawns over the past half-century.

A few minutes later, he’ll talk about hopping in a snowplow at 2 a.m. to do things the right way.

To curb salt use, brine and plows help, but people need to change, like Hajos’ crews are.

“There’s been a lot of focus on the plows and the brine and the measuring technology, which they’re all great, but they’re just tools,” Sexton said.

A lot of Sexton’s work has been around Lake George for the Fund for Lake George. Working with the Town of Hague, they cut salt use by a quarter and saved the town $66,000 a year.

Lately, he has met with officials in Lake Placid, where it all began.

There, salt is threatening the health of Mirror Lake. The amount of salt in the lake has hurt the lake’s ability to mix, which makes it harder for fish to survive there and may be partially responsible for an outbreak of harmful algae that appeared in the lake this fall.

While much of the focus has pointed the blame at DOT, there’s good reason to think the state is merely part of the problem. Around Mirror Lake, there’s more pavement in parking lots, sidewalks and driveways than state roads.

Sexton said that means it can’t all be the state’s fault. He pins blame on slip and fall lawsuits, which scared business owners into applying too much salt on their property. He said parking lots are now white from salt, not snow. That’s too much. He worked with Wegmans markets to safely cut salt use in half, saving the company money without endangering customers.

Ongoing coverage

Read up on the Explorer’s coverage of road salt

State transportation officials apparently believe there’s a lot of salt in parking lots, too. When Cuomo signed the salt study bill in December, he released a memo that said after “extensive discussions,” he had signed it on the condition that lawmakers tell the task force to “consider all sources of road salt contamination,” not just state road crews’ salt.

Just because they might agree on this, though, Sexton doesn’t give DOT a pass. Instead, he wonders why lawmakers, some environmental groups and the governor are still waiting to study a problem that has simple solutions.

“Everything they’ve wanted to study, we’ve done over the last five years,” Sexton said. “Why would you want to start that all over again?”

Salt is woven into New York’s history, for better and worse. Some of the early, contested and broken treaties between European settlers and Native Americans involved access to salt supplies around Syracuse. Today, New York is the nation’s third largest salt producer. Each year, the state generates some 17 billion pounds of salt worth about $600 million. The salt is used for all kinds of things, not just roads.

The proximity of large salt supplies to New York highways may have made it easier for salt to become the road chemical of choice two centuries later.

Around the Northeast and across the rest of New York, the clear trend has been to clear roads by dumping ton after ton of salt on them.

Even if the Olympics hadn’t sped up changes in the Adirondacks, New York had adopted a policy of clearing certain roads with salt in the early 1970s.

The sand that highway departments relied on before they switched to salt had its own problems. It might contain phosphorous, which also triggers algae blooms when sand washes into streams. Sand piles up, causing labor-intensive cleanups each spring. And, ultimately, sand doesn’t work as well as salt.

ARTICLE CREDIT: Adirondack Explorer

.

Recent Comments